The people in Jesus’ hometown synagogue in Nazareth are incensed, rise up to drive him out of town, “and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town had been built, to hurl him down headlong” (Lk 4:29). What got Jesus’ hometown crowd so twisted and contorted? Not only did he stand up earlier in this account of Luke and proclaim that he, the carpenter, was the fulfillment of the prophecy of Isaiah, but it was to the widow of Zarephath that Elijah came and Naaman the Syrian that Elisha healed.

All three of these points may be a big ho-hum to us, but they were a big deal to his people. Being a carpenter, more likely a simple day laborer, was not high on the social status ladder even in a poor town like Nazareth. The gospel writers even show the sensitivity of this. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus is mentioned in this scene as “the carpenter” (6:3), in Matthew, “the carpenter’s son” (13:39), and in today’s Gospel of Luke, “Joseph’s son” (4:22). By the time we get to Luke’s account, Jesus is not even associated with the trade of carpenter, how could someone of such simple and humble means assert the mantle of a prophet, let alone the Messiah?

Jesus does not go quietly in the night as the people’s wonder at his words turn to doubt and consternation. Jesus instead gives two seemingly obscure examples of people who receive God’s blessings. There were many widows and lepers in Israel, but it was to the widow of Zarephath that Elijah came and from Elisha that Naaman the Syrian received healing. The significance of these two people was that they were Gentiles, they were other, they were not part of the chosen people. Jesus is aligning himself in the prophetic tradition of Isaiah with the universal promise of God’s salvation that would also go out to the Gentile world. Jesus is invoking a choice that will consistently ripple throughout the remainder of his public ministry. People will either embrace his universal ministry or they will oppose it.

Jesus said to his own people, from his hometown, “Amen, I say to you, no prophet is accepted in his own native place” (Lk 4:24). We may look and wonder why Jesus would say such a thing and why after speaking of the widow of Zarephath and Naaman the Syrian that these same people were “filled with fury” and sought to throw him headlong out of town. One concrete reason is that Gentiles had been oppressing the Jewish people for generations. Beginning with the slavery they experienced in Egypt, the conquering of the ten northern tribes of Israel by the Assyrians, the Babylonians decimated the remaining southern tribes, exiled, and destroyed the Temple. After their return from exile, they suffered the occupying power of the Greeks, and during the time of Jesus’ preaching, the Romans. The hope of most Jews was that the Messiah would come to evoke a military uprising and overthrow their Roman occupiers.

Jesus’ hometown crowd was none too happy with Jesus’ universal message. We might too quickly judge them, but if we resist domesticating Jesus and allow ourselves to hear his words echoed today from our podiums and ambos, might we feel some of the same angst that the people of Nazareth felt? Who might we not be willing to welcome into the universal invitation of salvation that Jesus is still inviting us to experience in our day?

Would we embrace his message or begin to cross our arms and seethe? Would we too want to rise up and reject Jesus outright? If we are humble this Lent, we can walk up to Jesus and ask him to heal us of our own prejudices and biases, we can come to realize what gifts he has given us, and ask him to show us what ways we can bring glad tidings to those in our families, parishes, and communities. The choice is ours. Will we be an obstacle to Jesus’ healing or welcome the Holy Spirit to fall afresh upon us?

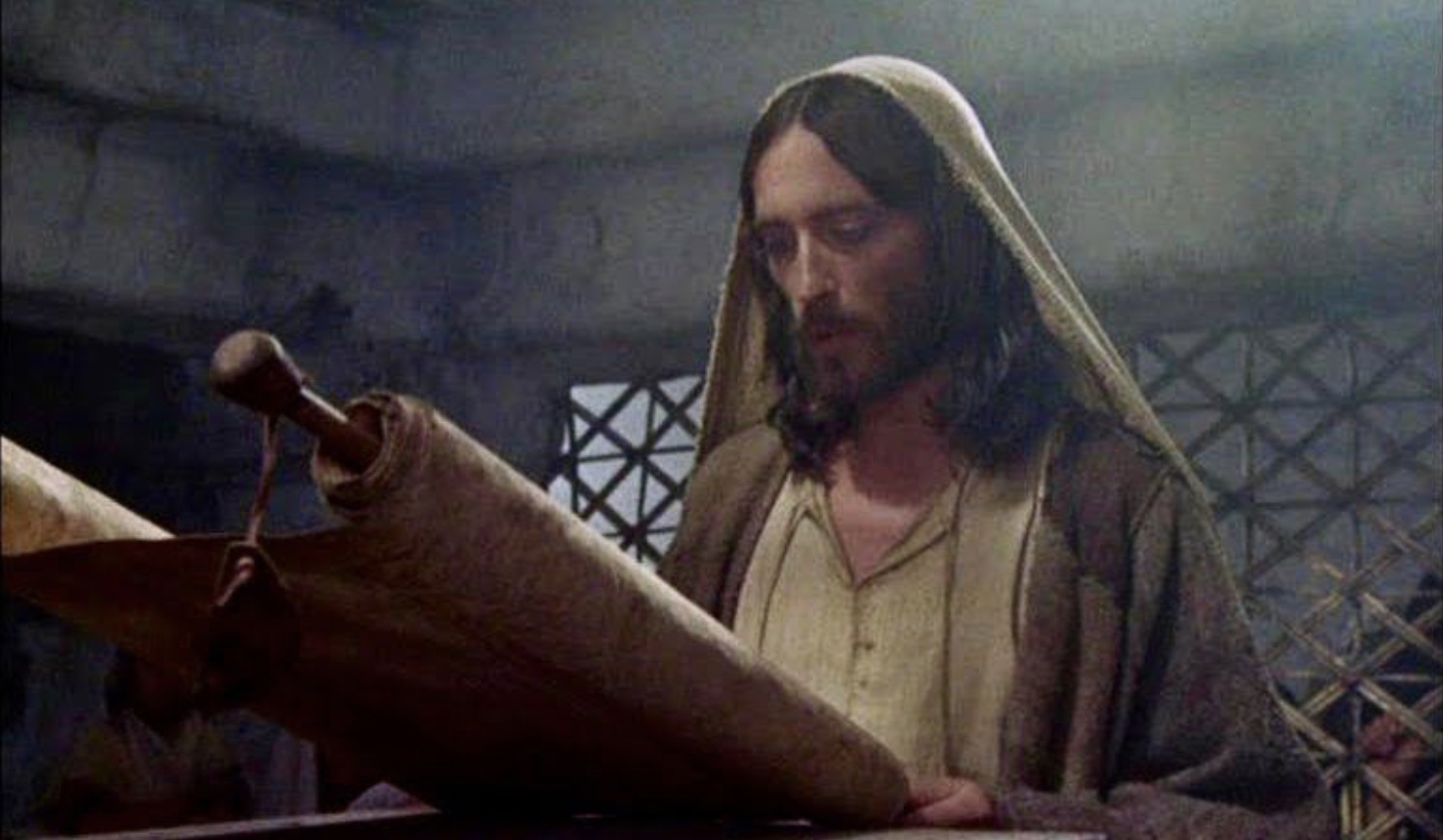

Photo: Jesus in the synagogue of Nazareth from Jesus of Nazareth, Franco Zeffirelli film, 1977